Richard Register is on the road again, leaving this week for Bhutan where he will meet with government officials about building ecocities in Panbang, a province of Zhemgang.

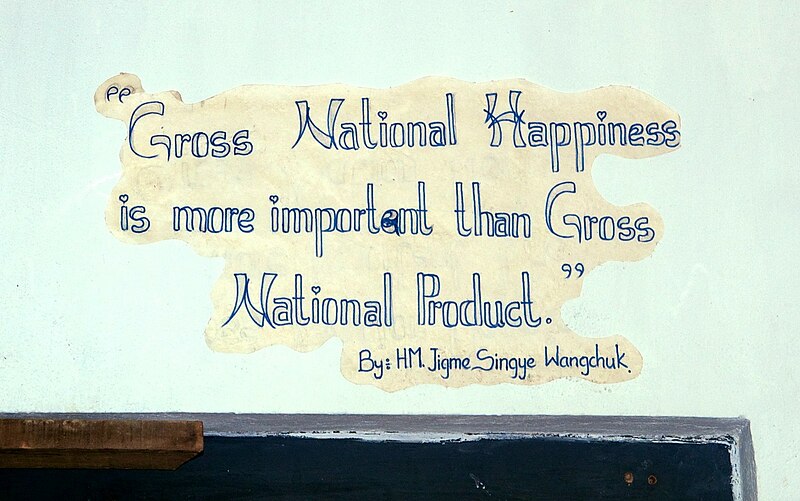

Bhutan is a small Buddhist county nestled in the Eastern crags of the Himalayas, commonly overshadowed in the news by its neighbors Tibet, Burma, China and India. Bhutan is most commonly known for its policy of Gross National Happiness (GHN), a metric introduced by King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuckn and used to measure the well-being of its citizens and guide the development of government policy. The four pillars of GNH are the promotion of sustainable development, preservation and promotion of cultural values, conservation of the natural environment, and establishment of good governance.

The GNH measures reflect Bhutan’s Buddhist foundations which emphasize the need for spiritual and moral development to coincide with material development. Bhutan is cautious about modernization, and justly so. Most countries have embraced the luxuries of modernity while degrading precious traditional values and our connection to nature.

Slogan on a wall in Thimphu’s School of Traditional Arts. Court. of Wikimedia Commons.

King Wangchuck broke with his father’s legacy and has opened Bhutan to modern changes little by little (Television appeared for the first time in 1999), hoping to adopt the benefits of new technology while avoiding the evils. The results are mixed – crime, materialism and dissatisfaction are rising, but not to the rates of most other countries. Some educated Bhutanese returning from educations in the West seek to lead the country in a unique blend of Buddhist values and Western practices.

For example, for every tree cut down they plant three new ones and claim to be the only country with proven negative CO2 production, that is, they absorb more CO2 out of the atmosphere than they put into it. Notably, English has been adopted as the universal language in Bhutan and is taught in the all free school system there (financed largely by sale of electricity from hydropower to India), a testament to the seriousness of their careful opening to modern ideas and ways.

Bhutan faces the enormous challenge of engaging reasonable change without being overwhelmed by the two gigantic countries on either side: China and India, India being their closest development partner to date. China crushed Buddhist Tibet and India ousted the Buddhist government of Sikkim, leaving Bhutan as the last country in the region with a King and traditional Tantric Buddhist religion at its core. At the same time, the King instituted a parliamentary system and has granted increasing legislative and administrative powers to a growing to date ever more democratic government.

The concept of the ecocity blends well with the philosophy of Bhutan. An ecocity is an opportunity to balance modern technology with these traditional values, blending simplicity and convergance to nature with infrastructure to support modern conveniences such as sanitation and electricity. Bhutan’s proposed ecocity will be situated near the south edge kingdom, north of the Gangiatic plane, and south of the foothills of the Himalayas. The idea is to build a leading city for “education, sport and eco-tourism” with an eye to bringing their GNH (Gross National Happiness) theme together with the leading ecocity project in the world.

Tashichho Dzong, a Buddhist monastery and seat of the Druk Desi, the head of Bhutan’s civil government. Court. Wikimedia Commons.

Richard’s vision is to take seriously the notion that happiness is a higher goal than maximum materialist consumption. It seems unthinkable that the general happiness and well-being of a people is not the highest priority indicator of their wealth. Yet Bhutan is the only country to explicitly say so. For the rest of us, the generation of paper and electronic numbers continues to be the applauded standard of well-being. We are left with other numbers to suggest the failings of our own gross national happiness: rising rates of disease, hospitalization, divorce, drug use and more.

Says Richard, “If we can design and build the sustainable city for a happy future – it would be such a large chunk of the solution, who could ask for anything more?”